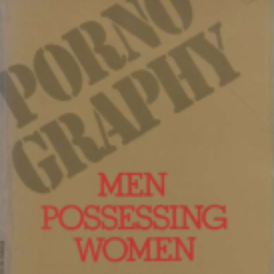

Obscenity is not a synonym for pornography. Obscenity is an idea; it requires a judgment of value. Pornography is concrete, "the graphic depiction of whores."

≡ Page 9

He is always in a panic, never large enough. But still, his self is immutable however much he may fear its ebbing away, because he keeps taking, and it is taking that is his immutable right and his immutable self. Even when he is obsessed with his need to be more and to have more, he is convinced of his right to be and to have.

≡ Page 14

The legend of male violence is the most celebrated legend of mankind and from it emerges the character of man: he is dangerous.

≡ Page 16

men have the power of naming, a great and sublime power. This power of naming enables men to define experience, to articulate boundaries and values, to designate to each thing its realm and qualities, to determine what can and cannot be expressed, to control perception itself.

≡ Page 17

Male supremacy is fused into the language, so that every sentence both heralds and affirms it. Thought, experienced primarily as language, is permeated by the linguistic and perceptual values developed expressly to subordinate women. Men have defined the parameters of every subject.

≡ Page 17

The male power of naming is upheld by force, pure and simple. On its own, without force to back it, measured against reality, it is not power; it is process, a more humble thing.

≡ Page 17

She says no; he claims it means yes. He names her ignorant, then forbids her education. He does not allow her to use her mind or body rigorously, then names her intuitive and emotional. He defines femininity and when she does not conform he names her deviant, sick, beats her up, slices off her clitoris (repository of pathological masculinity), tears out her womb (source of her personality), lobotomizes or narcotizes her (perverse recognition that she can think, though thinking in a woman is named deviant).

≡ Page 18

The world is his because he has named everything in it, including her. She uses this language against herself because it cannot be used any other way.

≡ Page 18

Marriage as an institution developed from rape as a practice. Rape, originally defined as abduction, became marriage by capture.

≡ Page 19

He is, he takes; she is not, she is taken.

≡ Page 26

In the photograph, the power of terror is basic. The men are hunters with guns. Their prey is women. They have caught a woman and tied her onto the hood of a car. The terror is implicit in the content of the photograph, but beyond that the photograph strikes the female viewer dumb with fear. One perceives that the bound woman must be in pain. The very power to make the photograph (to use the model, to tie her in that way) and the fact of the photograph (the fact that someone did use the model, did tie her in that way, that the photograph is published in a magazine and seen by millions of men who buy it specifically to see such photographs) evoke fear in the female observer unless she entirely dissociates herself from the photograph: refuses to believe or understand that real persons posed for it, refuses to see the bound person as a woman like herself. Terror is finally the content of the photograph, and it is also its effect on the female observer. That men have the power and desire to make, publish, and profit from the photograph engenders fear. That millions more men enjoy the photograph makes the fear palpable. That men who in general champion civil rights defend the photograph without experiencing it as an assault on women intensifies the fear, because if the horror of the photograph does not resonate with these men, that horror is not validated as horror in male culture, and women are left without apparent recourse.

≡ Page 27

Hunting as a sport suggests that these hunters have hunted before and will hunt again, that each captured woman will be used and owned, stuffed and mounted, that this right to own inheres in man’s relationship to nature, that this right to own is so natural and basic that it can be taken entirely for granted, that is, expressed as play or sport.

≡ Page 27

The fact of the photograph signifies the wealth of men as a class. One class simply does not so use another class unless that usage is maintained in the distribution of wealth. The female model’s job is the job of one who is economically imperiled, a sign of economic degradation. The relationship of the men to the woman in the photograph is not fantasy; it is symbol, meaningful because it is rooted in reality. The photograph shows a relationship of rich to poor that is actual in the larger society. The fact of the photograph in relation to its context — an industry that generates wealth by producing images of women abjectly used, a society in which women cannot adequately earn money because women are valued precisely as the woman in the photograph is valued — both proves and perpetuates the real connection between masculinity and wealth. The sexual-economic significance of the photograph is so simple that it is easily overlooked: the photograph could not exist as a type of photograph that produces wealth without the wealth of men to produce and consume it.

≡ Page 29

The pornographic image explicates the advertising image, and the advertising image echoes the pornographic image.

≡ Page 30

The excitement is precisely in the nonconsensual character of the event. The hunt, the ropes, the guns, show that anything done to her was or will be done against her will. Here again, the valuation of conquest as being natural — of nature, of man in nature, of natural man — is implicit in the visual and linguistic imagery.The power of sex, in male terms, is also funereal. Death permeates it. The male erotic trinity — sex, violence, and death — reigns supreme. She will be or is dead. They did or will kill her. Everything that they do to or with her is violence. Especially evocative is the phrase “stuffed and mounted her, ” suggesting as it does both sexual violation and embalming.

≡ Page 30

In the photograph, all visual significance is given to the ass of the woman on her knees, which is in the foreground, exaggerated by the light markedly on it, and to its echo, the raised buttock of the woman reclining. The camera is the penile presence, the viewer is the male who participates in the sexual action, which is not within the photograph but in the perception of it. The photograph does not document lesbian lovemaking; in fact, it barely resembles it. The symbolic reality of the photograph — which is vivid — is not in the relationship between the two women, which not only does not provoke but actually prohibits any recognition of lesbian eroticism as authentic or even existent. The symbolic reality instead is expressed in the posture of women exposed purposefully to excite a male viewer. The ass is exposed and vulnerable; the camera has taken it; the viewer can claim it.

≡ Page 46

The photograph is the ultimate tribute to male power: the male is not in the room, yet the women are there for his pleasure. His wealth produces the photograph; his wealth consumes the photograph; he produces and consumes the women. The male defines and controls the idea of the lesbian in the composition of the photograph. In viewing it, he possesses her. The lesbian is colonialized, reduced to a variant of woman-as-sex-object, used to demonstrate and prove that male power pervades and invades even the private sanctuary of women with each other. The power of the male is affirmed as omnipresent and controlling even when the male himself is absent and invisible. This is divine power, the power of divine right to divine pleasure, that pleasure accurately described as the sexual debasing of others inferior by birth. In private, the women are posed for display. In private, the women still sexually service the male, for whose pleasure they are called into existence. The pleasure of the male requires the annihilation of women’s sexual integrity. There is no privacy, no closed door, no self- determined meaning, for women with each other in the world of pornography.

≡ Page 47

Virginia Woolf wrote: “I detest the masculine point of view. I am bored by his heroism, virtue, and honour. I think the best these men can do is not to talk about themselves anymore. ” Men have claimed the human point of view; they author it; they own it. Men are humanists, humans, humanism. Men are rapists, batterers, plunderers, killers; these same men are religious prophets, poets, heroes, figures of romance, adventure, accomplishment, figures ennobled by tragedy and defeat. Men have claimed the earth, called it Her. Men ruin Her. Men have airplanes, guns, bombs, poisonous gases, weapons so perverse and deadly that they defy any authentically human imagination. Men battle each other and Her

≡ Page 48

Becoming a man requires that the boy learn to be indifferent to the fate of women. Indifference requires that the boy learn to experience women as objects. The poet, the mystic, the prophet, the so-called sensitive man of any stripe, will still hear the wind whisper and the trees cry. But to him, women will be mute. He will have learned to be deaf to the sounds, sighs, whispers, screams of women in order to ally himself with other men in the hope that they will not treat him as a child, that is, as one who belongs with the women.

≡ Page 49

The boy seeks to emulate the father because it is safer to be like the father than like the mother. He learns to threaten or hit because men can and men must. He dissociates himself from the powerlessness he did experience, the powerlessness to which females as a class are consigned. The boy becomes a man by taking on the behaviors of men — to the best of his ability.

The boy escapes, into manhood, into power. It is his option, based on the social valuation of his anatomy. This route of escape is the only one now charted.

But the boy remembers, he always remembers, that once he was a child, close to women in powerlessness, in potential or actual humiliation, in danger from male aggression. The boy must build up a male identity, a fortressed castle with an impenetrable moat, so that he is inaccessible, so that he is invulnerable to the memory of his origins, to the sorrowful or enraged calls of the women he left behind. The boy, whatever his chosen style, turns martial in his masculinity, fierce, stubborn, rigid, humorless. His fear of men turns into aggression against women. He keeps the distance between himself and women unbridgeable, transforms women into the dreaded She, or, as Simone de Beauvoir expresses it, “the Other. ” He learns to be a man — poet man, gangster man, professional religious man, rapist man, any kind of man — and the first rule of masculinity is that whatever he is, women are not. He calls his cowardice heroism, and he keeps women out — out of humanity (fabled Mankind), out of his sphere of activity whatever it is, r out ofall that is valued, rewarded, credible, out of the diminishing realm of his own capacity to care. Women must be kept out because wherever there are women, there is one haunting, vivid memory with numberless smothering tentacles: he is that child, powerless against the adult male, afraid of him, humiliated by him.

≡ Page 50

Men develop a strong loyalty to violence. Men must come to terms with violence because it is the prime component of male identity. Institutionalized in sports, the military, acculturated sexuality, the history and mythology of heroism, it is taught to boys until they become its advocates — men, not women. Men become advocates of that which they most fear. In advocacy they experience mastery of fear. In mastery of fear they experience freedom. Men transform their fear of male violence into a metaphysical commitment to male violence. Violence itself becomes the central definition of any experience that is profound and significant.

≡ Page 51

Some men will use language as violence, or money as violence, or religion as violence, or science as violence, or influence over others as violence. Some men will commit violence against the minds of others and some against the bodies of others. Most men, in their life histories, have done both.

≡ Page 52

In male culture, police are heroic and so are outlaws; males who enforce standards are heroic and so are those who violate them.

≡ Page 53

In adoring violence — from the crucifixion of Christ to the cinematic portrayal of General Patton — men seek to adore themselves, or those distorted fragments of self left over when the capacity to perceive the value of life has been paralyzed and maimed by the very adherence to violence that men articulate as life’s central and energizing meaning.

≡ Page 53

Women who were molested as children also experience confusion as to what they really wanted when the adult male exercised his sexual will on them, but must, as a condition of forced femininity, accept the male as constant aggressor and forced sex as normative. In women, this often results in a passivity bordering on narcolepsy, morbid self-blame, and punishing self-hatred. Men molested as children resolve their confusion through action: in crossing over to the adult side, they remove themselves from the pool of victims. Since as adults they can experience the commission of forcible sex with others as freedom, they can say, as poet Allen Ginsberg did on a Boston television show, that they were molested as children and liked it. This is the public stance of the boy who has become the man, no matter what his private or secret ambivalences might be. Unlike women, men as adults are not likely to be molested again.

≡ Page 58

Consent, properly understood in a society where men have turned both desire and freedom into dirty jokes, is a reality only between or among peers, and the poor and the rich are never peers. And boys, in particular poor boys, are not and cannot be the peers of adult men.

≡ Page 59

Male perceptions of women are askew, wild, inept. Male renderings of women in art, literature, psychology, religious discourses, philosophy, and in the common wisdom of the day, whatever the day, are bizarre, distorted, fragmented at best, demented in the main. Everything is done to keep women out of the perceptual field altogether, but, like insects, women creep in; find the slightest chink in the male armor and watch her, odious thing, crawl in. Even this presence, on hands and knees as it were, is so disorienting, so fiercely threatening, that attributions of malice must be made — immediate, intense, slanderous, couched in language that conveys the man’s absolute authority to speak. In male reality, women cannot enter male consciousness without violating it. The male is contaminated and distressed by any contact with woman-not-as-object. He loses ground. His own masculinity cannot withstand what he regards as an assault unless he steps on the uppity thing, crushes it by hook or by crook, by insult, open hand flat against the face or clenched fist crushed into it.

≡ Page 64

Every attempt she makes to reclaim the humanity he has stolen from her makes her subject to insult, ridicule, and abuse. In his view, she is not a woman unless she acts like a woman as he has defined woman. His definition need not be coherent. It is never scrutinized for logic or consistency or even threadbare common sense. He can theorize, fantasize, call it science or art; whatever he says about women is true because he says it. He is the authority on what she is because he has made her, cut away at her as if she were a piece of stone until the prized inanimate object is extracted.

≡ Page 65

Anything, including memory or conscience, that pulls a man toward women as humans, not as objects and not as monsters, does endanger him. But the danger is always from other men. And no matter how afraid he is of those other men, he has taken a vow — one for all and all for one — and he will not tell. Women are scapegoated here too, called powerful by men who know only too well how powerless women are — know it so well that they will tell any lie and commit any crime so as not to be touched by the stigma of that powerlessness.

≡ Page 66

Everything is split apart: intellect from feeling and/or imagination; act from consequence; symbol from reality; mind from body. Some part substitutes for the whole and the whole is sacrificed to the part. So the scientist can work on bomb or virus, the artist on poem, the photographer on picture, with no appreciation of its meaning outside itself; and even reduce each of these things to an abstract element that is part of its composition and focus on that abstract element and nothing else — literally attribute meaning to or discover meaning in nothing else. In the midtwentieth century, the post-Holocaust world, it is common for men to find meaning in nothing: nothing has meaning; Nothing is meaning. In prerevolutionary Russia, men strained to be nihilists; it took enormous effort. In this world, here and now, after Auschwitz, after Hiroshima, after Vietnam, after Jonestown, men need not strain. Nihilism, like gravity, is a law of nature, male nature. The men, of course, are tired. It has been an exhausting period of extermination and devastation, on a scale genuinely new, with new methods, new possibilities. Even when faced with the probable extinction of themselves at their own hand, men refuse to look at the whole, take all the causes and all the effects into account, perceive the intricate connections between the world they make and themselves. They are alienated, they say, from this world of pain and torment; they make romance out of this alienation so as to avoid taking responsibility for what they do and what they are. Male dissociation from life is not new or particularly modern, but the scale and intensity of this disaffection are new. And in the midst of this Brave New World, how comforting and familiar it is to exercise passionate cruelty on women. The old-fashioned values still obtain.

≡ Page 67

There are only the old values, women there for the taking, the means of taking determined by the male. It is ancient and it is modern; it is feudal, capitalist, socialist; it is caveman and astronaut, agricultural and industrial, urban and rural. For men, the right to abuse women is elemental, the first principle, with no beginning unless one is willing to trace origins back to God and with no end plausibly in sight. For men, their right to control and abuse the bodies of women is the one comforting constant in a world rigged to blow up but they do not know when.

In pornography, men express the tenets of their unchanging faith, what they must believe is true of women and of themselves to sustain themselves as they are, to ward off recognition that a commitment to masculinity is a double-edged commitment to both suicide and genocide. In life, the objects are fighting back, rebelling, demanding that every breath be reckoned with as the breath of a living person, not a viper trapped under a rock, but an authentic, willful, living being. In pornography, the object is slut, sticking daggers up her vagina and smiling. A bible piling up its code for centuries, a secret corpus gone public, a private corpus gone political, pornography is the male’s sacred stronghold, a monastic retreat for manhood on the verge of its own destruction.

≡ Page 68

Pornography is the holy corpus of men who would rather die than change.

≡ Page 68

Pornography reveals that male pleasure is inextricably tied to victimizing, hurting, exploiting; that sexual fun and sexual passion in the privacy of the male imagination are inseparable from the brutality of male history. The private world of sexual dominance that men demand as their right and their freedom is the mirror image of the public world of sadism and atrocity that men consistently and self- righteously deplore. It is in the male experience of pleasure that one finds the meaning of male history.

≡ Page 69

Those leftists who champion Sade might do well to remember that prerevolutionary France was filled with starving people. The feudal system was both cruel and crude. The rights of the aristocracy to the labor and bodies of the poor were unchallenged and not challengeable. The tyranny of class was absolute. The poor sold what they could, including themselves, to survive. Sade learned and upheld the ethic of his class.

≡ Page 72

The use of money to buy women is apparently mesmerizing. It magically licenses any crime against women. Once a woman has been paid, crime is expiated. That no real harm was done, no matter what actually was done, is a particularly important theme.

≡ Page 85

The savagery of his life created the strange desperation of hers. The nightmare of her life has been lost in the celebration of his.

≡ Page 88

Justine and Juliette are the two prototypical female figures in male pornography of all types. Both are wax dolls into which things are stuck. One suffers and is provocative in her suffering. The more she suffers, the more she provokes men to make her suffer. Her suffering is arousing; the more she suffers, the more aroused her torturers become. She, then, becomes responsible for her suffering, since she invites it by suffering. The other revels in all that men do to her; she is the woman who likes it, no matter what the “it.” In Sade, the “attitude” (to use Barthes’s word) on which one’s status as victim or master depends is an attitude toward male power. The victim actually refuses to ally herself with male power, to take on its values as her own. She screams, she refuses. Men conceptualize this resistance as conformity to ridiculous feminine notions about purity and goodness; whereas in fact the victim refuses to ally herself with those who demand her complicity in her own degradation. Degradation is implicit in inhabiting a predetermined universe in which one cannot choose what one does, only one’s attitude (to scream, to discharge) toward what is done to one. Unable to manifest her resistance as power, the woman who suffers manifests it as passivity, except for the scream.

≡ Page 96

Sade’s importance, finally, is not as dissident or deviant: it is as Everyman, a designation the power-crazed aristocrat would have found repugnant but one that women, on examination, will find true. In Sade, the authentic equation is revealed: the power of the pornographer is the power of the rapist/batterer is the power of the man.

≡ Page 100

A man must function as the human center of a chattel-oriented sensibility, surrounded by objects to be used so that he can experience his own power and presence. He must not reduce himself to the level of women, for instance, by becoming an object for another man. This degrades the whole male sex, which is inappropriate.

≡ Page 104

The inevitable and intrinsic cruelty involved in turning a person into an object should be apparent, but since this constricting, this undermining, this devaluing, is normative, no particular cruelty is recognized in it. Instead, there is only normal and natural cruelty — the normal and natural sadism of the male, happily complemented by the normal and natural masochism of the female. Each psychologist puts this view forth in his own quiet, unassuming way. Anthony Storr, considered an expert on violence, suggests that “[i]t is probably true that men are generally more ‘sadistic’ and women more masochistic. ’ . . . there are many women who nag unmercifully in the hope that their man will finally treat them with the force that they find exciting. ” The object is allowed to desire if she desires to be an object: to be formed; especially to be used.

≡ Page 109

The object, the woman, goes out into the world formed as men have formed her to be used as men wish to use her. She is then a provocation. The object provokes its use. It provokes its use because of its form, determined by the one who is provoked.

≡ Page 111

Poetry, the genre of purest beauty, was born of a truncated woman: her head severed from her body with a sword, a symbolic penis, so that poetry is born not only of a dead woman but of one sadistically mutilated. Poe, whose debt to Perseus cannot be overestimated, wrote that “[t]he death of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world.” ”The function of beauty in the realm of the so-called erotic was further elucidated by Bataille when he wrote: “Beauty is desired in order that it may be befouled; not for its own sake, but for the joy brought by the certainty of profaning it.” Beauty, then, consistently has meaning in the sphere of female death or violation.

≡ Page 117

The intense and obsessive use of person as object is seen as the solution to man’s alienation — not as the source of it nor as one of its most numbing manifestations. Not only does “love. . . increase [the] self by means of the object”; but the fact of objectification — this diminished capacity to perceive and respond to life — is viewed as a key and dynamic element of individuality. Since men characteristically respond only to sexual fragments, bits and pieces, slivers of flesh costumed this way or that, this very incapacity is consistently transformed into one of love’s defining virtues. Krafft-Ebing, a pioneering sexologist currently out of fashion (unlike Kinsey and Ellis) because his goal was to move sexual deviation out of the realm of the criminal into the realm of the medical (not into the realm of the normal), enunciated a still-current appraisal of the value of objectification:

"In the considerations concerning the psychology of the normal sexual life in the first chapter of this work it was shown that, within psychological limits, the pronounced preference for a certain portion of the body of persons of the opposite sex, particularly for a certain form of this part, may attain great psychosexual importance. Indeed, the especial power of attraction possessed by certain forms and peculiarities for many men — in fact, the majority — may be regarded as the real principle of individualism in love."

The automatic, predetermined, fixed, intransigent response to a particular form or part of the body is supposed to be a manifestation of individuality rather than a paralyzation of individuality. The male’s individuality, in effect, can be reckoned by how little he responds to, how little he perceives, how little he values. Sexual myopia, then, becomes the paradigm for individuality.

≡ Page 121

In pornography, his sense of purpose is fully realized. She is the pinup, the centerfold, the poster, the postcard, the dirty picture, naked, half-dressed, laid out, legs spread, breasts or ass protruding. She is the thing she is supposed to be: the thing that makes him erect. In literary and cinematic pornography, she is taught to be that thing: raped, beaten, bound, used, until she recognizes her true nature and purpose and complies — happily, greedily, begging for more. She is used until she knows only that she is a thing to be used. This knowledge is her authentic erotic sensibility: her erotic destiny. The more she is a thing, the more she provokes erection; the more she is a thing, the more she fulfills her purpose; her purpose is to be the thing that provokes erection. She starts out searching for love or in love with love. She finds love as men understand it in being the thing men use.

≡ Page 128

At the same time, essential to this gratification on some level is the illusion that the women are not controlled by men but are acting freely. The photographs of the two women are a peek through a keyhole. The conceit is that since the male is not in the photographs, the women are doing what they want to do willfully and for themselves: “When Katherina was asked why she was having her pubic hair styled, she told us that it was purely for her own self. ” What women in private want to do just happens to be what men want them to do. This is the meanest theme of pornography: the elucidation of what men insist is the secret, hidden, true carnality of women, free women. When the secret is revealed, the whore is exposed.

≡ Page 136